In today’s world, the word feminism sometimes carries negative connotations. I prefer to think of feminism as “learning how to stand up for ourselves.” To say no, that doesn’t work for me. We’ve seen that happen in our time as women joined the Me Too movement and as many continue to march for the freedom to choose what happens to our bodies.

The world of feminism first came to me in the mid-60s when I moved to San Francisco and started my first real job: secretary to the manager of the New York based firm, Metromedia. Our company provided bus advertising throughout the Bay Area. There were salesmen, the accountant, and the secretaries—plus the “barn” where older, experienced men pasted the enormous ads onto the sides of busses and trolley streetcars.

In 1967, I was twenty-seven and a single mom with two young sons. I’d already experienced discrimination when Marin County apartments refused me a rental because 1) I was a single mother and 2) my children were boys. In San Francisco, my sons and I found an attached home in the Miraloma neighborhood. I was impressed by the ethnic diversity. The school was within two blocks and my young sons could then go to a neighbor’s for after-school care. Even at that time, childcare cost the equivalent of my rent, $195 a month. Child support and my salary only went so far.

But I was freed from an unhappy marriage, the first step in taking care of myself. Was it easy? No. Was it hard on my children? Yes. Did I have regrets: never.

From My Window, Tides of Change

Across town, there was a lot going on in the Haight Ashbury, and Joan Didion was covering it. Located in my new job in the financial district and my new home across town, I was busy reading both Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl. I needed both books for similar reasons—I was in search of who I really was now that I’d shed the Leave It to Beaver ideal. I knew that once I walked away from my traditional roles, I couldn’t walk back.

Personal freedom can be intoxicating, and that’s what it was for me. I started a writing course at the local junior college and typed away on an old standard Royal I managed to find in my office where we now typed on Selectrics. My stories encapsulated recent experiences; one in particular was about hiking in the Big Sur and experiencing the worst terror I’d ever felt. Meanwhile, when my sons were home with me for the weekend, I’d leave the typewriter long enough to make peanut butter and jelly sandwiches while they played nearby in the same room.

Looking back on that time, I recall how terrified I was at San Francisco State when the new feminists showed up in their leathers with their motorcycles parked outside the building. We were all in the same creative writing graduate program and what they had to say was far more radical than my tentative toe into the waters of rebellion. I also remember how those meager beginnings became a prototype for where I am today at 82 years old. Except for the absence of my sons, I’m still typing, still living alone and, as I tell my still-adorable sons, I’m the happiest I’ve ever been. The freedom to be me, to choose how I spend my day, who I relate to, how I manage my money and calendar continues to be rewarding in and of itself.

The Shoulders We Stand On

What does this have to do with feminism? In my recent novel, Forever Blackbirds, the female protagonist (modeled on my maternal grandmother) has few options. As she says in the novel, she “would be lucky if anyone married her.” She’d suffered terrible facial scarring and, consequently, felt undesirable. She gladly accepted her role as wife and mother to the one man who chose her. Without other options, she stayed in a mostly loveless marriage. But her religious faith provided the binding that kept her walking into each day. She did the cooking, cleaning, baking and childcare; she was obedient to her husband. This was her role in life. She did not complain. “This is the way it is.”

Her daughter, my mother, did likewise. A challenging marriage, five children, and she never complained. Like her mother before her, she also never lost her sense of humor. I often quote her to my sister Peggy: I wish I’d been born rich instead of so good looking. It makes us laugh every time. Mom was forever stoic and faithful in her role. She often said, “You make your bed; you lie in it.”

The San Francisco experience of my twenties never left me. I recall my mother’s near horror when I’d pile my sons and her youngest daughter into my VW bug and take off for South Dakota where I’d grown up. My second husband never once suggested or challenged otherwise. He may have been as intimidated by my strong will as my mother was.

When I look back on my grandmother and my mother’s life, I’m often amazed at how hard the physical work was. Just doing laundry for a large family was an all-day chore. I don’t recall if my grandmother had a washing machine or not, but I suspect she did the laundry with an old-fashioned wash board and Fels Naptha soap that she shaved into the water. That doesn’t begin to underscore the fact that she carried water from a well into the kitchen where all life began and ended in her house. I recall my own mother standing at the wringer wash machine feeding the clothes, one piece at a time, into the wringer to eliminate the excess water. I was there the day she accidentally caught her arm in the wringer. Maybe she was daydreaming like we all do when performing repetitive tasks. Those were also the days when she sat at a mangle and ironed the sheets. Most women today wouldn’t know what those household “savers” were. Squeezing the color into oleo-margarine. Dry cleaning winter garments in the back yard with a gasoline equivalent. Wringing the chicken’s neck before plucking and cleaning out the insides. Fortunately, my father was not a hunter, or she might have had to “clean out” larger game.

Sometimes I’ve wondered if the generation of women who have come behind me really understand how far we’ve come and whose shoulders we stand on. Though not everyone grew up in a post-Depression, post-World War I survival society, I’m certain that their mothers could tell stories about how they experienced their lives in yesteryear compared to today.

Dreams the Pill Made Possible

World War II became the landmark for women moving into men’s work, for women experiencing freedom and responsibility they hadn’t known before. I recall a great aunt telling me about the Suffragette movement early in the twentieth century. How she marched and supported women’s rights, primarily the right to vote. These facts make it easy to understand the fight to claim back the bodily rights Roe vs. Wade provided us. There’s an unwillingness to step backward and accept the inability to own our own bodies. The enormous outcry gives testimony to what has been gained.

I was twenty-three when the pill became available to American women. My then-husband was a senior in medical school. The student’s wives were some of the first to be offered this new method of birth control. For the many who had found themselves in a marriage due to pregnancy and illegal abortion laws, the pill spelled sexual freedom in a way we had never known before. WE were now in charge of our bodies and, consequently in charge of our very lives. I recall I had just given birth to our second son. The pill meant I was done. Two children were enough. I was now a free woman. Free to earn my own living. Free to choose to be sexual or not. Free to be the me I had dreamed of being at sixteen.

I have great compassion for my mother and grandmothers: they had no choice but to continue to have children. I remember how Mom said she longed to go to nurse’s training and have a nursing career. In a post-Depression world, the finances weren’t there. But the dream lingered in the same way I dreamed at eighteen of a career in New York’s publishing world. Many of our dreams flourished and then died before the pill made dreams possible.

It took the completion of two novels for me to realize that my writer’s “mission” is to re-create the lives of women moving toward agency in their own lives. That often means financial freedom, something too many women continue to struggle with.

We Won’t Step Back

In my debut novel, About the Carleton Sisters, Lorraine, the eldest, personifies the “dutiful daughter” who eventually pays for her sense of duty with a particular kind of loneliness. Julie, her year-younger sister, escaped the town and expected roles when she was seventeen. She enjoyed a thirty-year career as a dancer. But I think the most sorrow-filled character in the novel is the mother, Dotty. She gave up a banking career and followed the given formula only to end up unexpectedly abandoned and, as a consequence, bitter. I’ve too often seen this in my psychotherapy practice. The question then becomes, “What now?” Too often, the older we get, the harder it is to answer the question.

To live without regrets is a self-compassionate act. As a writer, my life has given me enough grist for the fiction mill to carry me through another 82 years. Because I’m a woman who has been lucky enough to experience freedom of choice, I want that for my granddaughters and for all women. We are both the pioneers and the heroes of tomorrow. We won’t step back. Watch us!

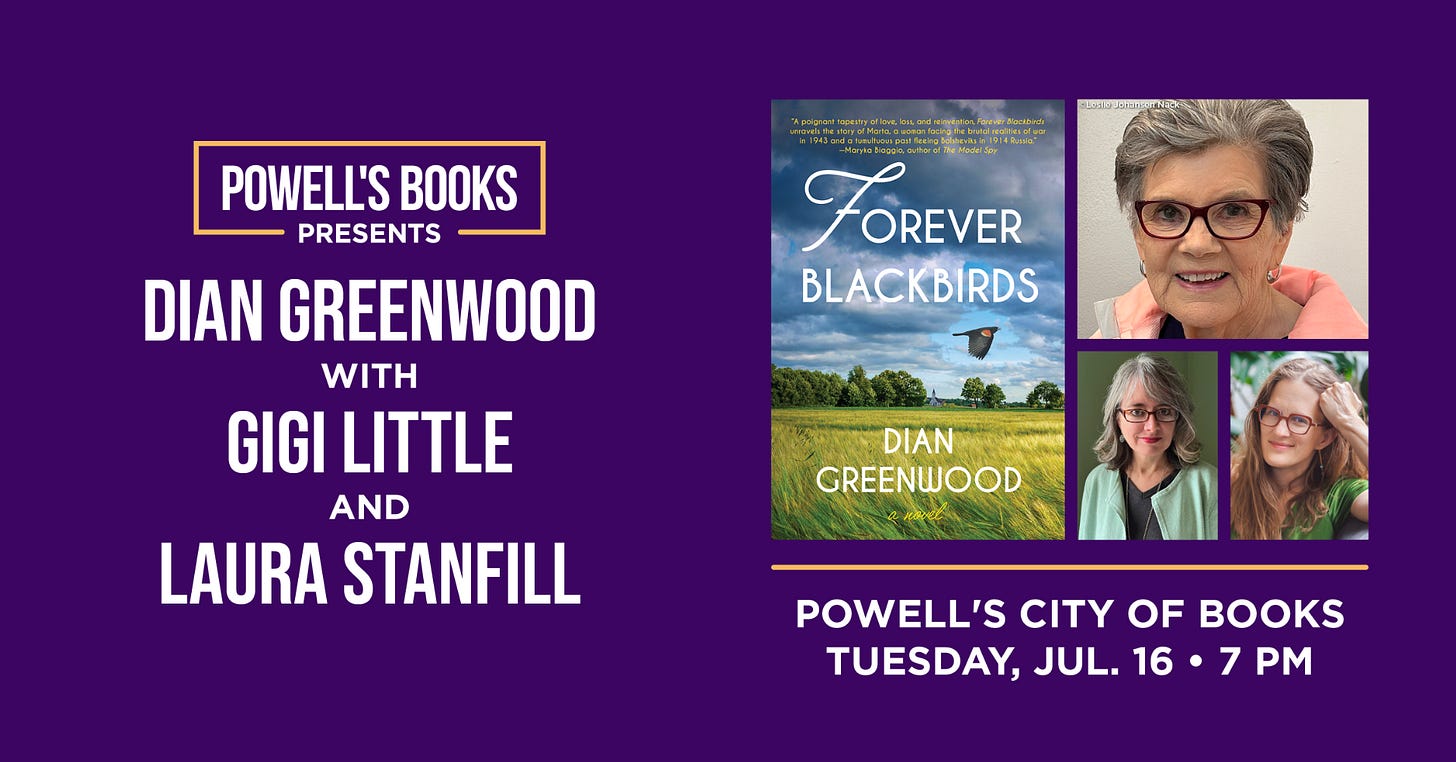

Visit diangreedwood.com to learn more about Forever Blackbirds and About the Carleton Sister.

P.S., if you’re local to Portland, be sure to come by Powell’s City of Books for a reading on July 16. Free to the public; hope to see you there!

Love these pictures, too! Can't wait to see you Tuesday.

An excellent essay, Dian. You and I have some of the same memories of how life was for our mothers and their mothers before them. All of it so beautifully depicted in your new book. A hard life, then. We made some serious noise during the second wave seventies, and we're not stopping.