The Seldom-Told Story of Germans in Russia

From an empress's invitation to a communist revolution

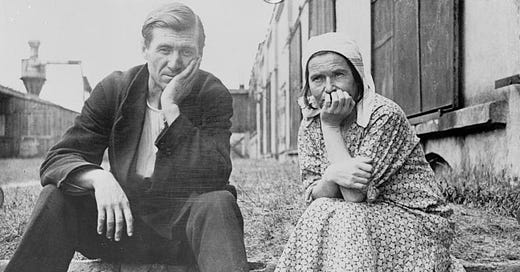

When I began to write Forever Blackbirds, all I had to start with were the stories my grandmother told me when I was five or six-years old and then, years-later, a single conversation at a round table with my not-well-known cousins following a family memorial. With these small threads and a little historical knowledge, I entered a writing retreat in 2008 where, on Day 2, I broke my ankle and was confined to my son’s cabin for my month-long retreat.

The thread that always leads me into a story is a character. I already had my grandmother. But who was she as a young girl, and who was this family with whom she escaped from Russia? Why were they near the Black Sea to begin with?

My son Brian has always had an interest in genealogy. He has traced one of our family root back to reindeer herders in the far northern Scandinavian countries. The particular branch around the Black Sea interested him since both of my maternal grandparents came from different villages just northwest and northeast of Odessa, Russia. Perhaps the simplest but most comprehensive explanation I found for why so many Germans lived in Russia came from an article from North Dakota State University written by Michael M. Miller.

Catherine the Great’s Invitation

I was already aware that the Germans who emigrated to Russia had come at the invitation of Czarina Catherine the Great, a former German princess. She possessed large tracts of land around the Volga River. On July 22, 1763, she issued a manifesto inviting foreigners to settle these lands with the idea of cultivating what was uncultivated land. She induced these foreigners with the following rights and privileges:

1) Free transportation to Russia.

2) The right to settle in segregated colonies.

3) Free land and the necessary tax-free loans to establish themselves.

4) Religious freedom and the right to build their own churches (their own schools was implied).

5) Local self-government.

6) Exemption from military or civil service.

7) The right to leave Russia at any time.

8) Therefore mentioned rights and privileges were guaranteed not only to the incoming settlers but also to their descendants forever.

“A Brief History of the Germans from Russia,” Michael M. Miller,

Germans from Russia Bibliographer, NDSU Libraries,

Fargo, North Dakota

What I learned from Mr. Miller was that the Germans came in different waves and at different times, settling in different regions. Some settled along the Volga River, others on the Crimean Peninsula, others in the Caucasus and the Ukraine as well as those who chose the Black Sea.

Who Were the Black Sea Germans?

I knew from my son’s pursuit of our genealogy that my grandmother’s people had settled in the small village of Kessel, just northwest of Odessa in the Glueckstal German Villages & Hoffnungstal District. My grandfather was traced to a village northeast of Odessa in the Cherson region called Rohrbach. These Germans lived in their own villages with their fellow Germans. While they separated themselves from the Russians, over time they were forced to relate to their countrymen.

Revolution and Rescinded Promises

All went well until nearly two centuries later when, after the czars had been assassinated, the socialists began to emerge as the new political power. In the wake of this change, Russians wanted their land back. They created laws that eliminated the original promises, particularly that the German sons would be free of military conscription. As they began to take the land back, often by forcing the Germans out, the threat to their freedom forced the Germans to look elsewhere for more peaceful homes. According to my cousin, the turning point for our forefathers was when the neighboring farms were burned out. The threat of conscription and the fear of being forced out compelled my great grandfather, a very wealthy farmer by report, to emigrate to the United States, a reported haven of freedom and safety.

Crossing the Atlantic

My grandmother emigrated with her family to the United States in 1900. She was three years old. From her stories, they traveled in steerage, their wealth primarily in the land they reluctantly left behind. Grandma Maggie said she sang songs on deck, holding out her cup in hope of coins. My grandfather, her husband, emigrated later. I know he served in WWI as did his twin brother. Because my grandmother’s maiden name was Rosin, I long suspected that she was originally Jewish. Research indicated that she was evangelical, both in Russia and as I knew her during her lifetime.

Assimilation and Family Ties

From family stories and what I observed throughout my childhood and, later, returning to research at the Germans from Russia Center in Bismarck, North Dakota, their particular enclave settled in central North Dakota. Receiving land grants and knowing how to cultivate the land, they formed small communities, their common language and religious faith binding them. My mother said she failed first grade because her family spoke only German at home and the school’s classes were in English. Assimilation was the goal, something they may have resisted in Russia, though in America, free from threats and oppression, they were likely more willing to comply.

These are clannish people. Today, we would say tribal. It must have been scandalous to my grandparents when my father, a non-German whose mother was Catholic, wandered into town with the Northern Pacific Railroad and fell in love with my mother. No wonder my parents eloped to my father’s hometown, Glendive, Montana, after knowing each other for six weeks.

I hope that this bird’s eye view helps the reader understand some of the “seeds” I worked with and expanded into the world I created and the family that populates Forever Blackbirds. There’s more to come. In the next Substack, we’ll look at my research regarding Ellis Island and the immigration impediments in the early 1900’s that were as real then as they are today.

Has knowing your ancestors affected or influenced your view of family? If so, tell share your story. I’d love to hear from you.